By: Rebecka Lundgren, Meredith Pierce, Anita Raj, Namratha Rao

By: Rebecka Lundgren, Meredith Pierce, Anita Raj, Namratha Rao

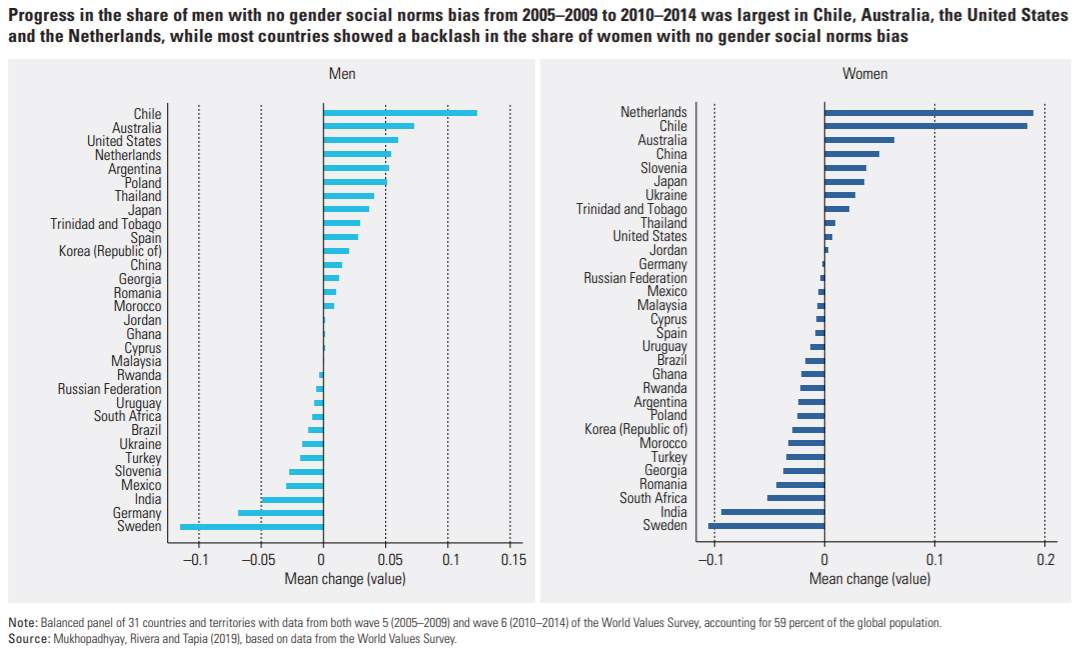

The most striking and disturbing finding of this new work is that these restrictive gender norms have, in fact, increased rather than decreased across the globe. (See graphs below, taken from GSNI Report). These findings contrast sharply with continued improvements on key gender equality indicators (e.g. girls’ education, women’s political participation) in this same period. This indicates that, even while we are seeing face-value improvements in women and girls’ access to socio-economic opportunities, restrictive gender norms are pervasive.

Click to view full-size. Figure taken from UDNP’s 2020 Human Development Perspectives Tackling Social Norms: A game changer for gender inequalities report.

Click to view full-size. Figure taken from UDNP’s 2020 Human Development Perspectives Tackling Social Norms: A game changer for gender inequalities report.

How does GSNI measure norms?

This new index focused on gender norms is vitally important to track progress on Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieving Gender Equality and Empowerment of All Women and Girls. Unfortunately, the index is also limited by relying on component indicators pulled from large-scale surveys that are not norms, but are individual attitudes and beliefs. This is not a flaw of the index per se, but of the indicators we have available as relates to gender norms. Social norms should be measured for a given group as:

While attitudes, beliefs and norms are all related to gender equity, they are distinct constructs and should be measured as such. Applied to gender norms, this might change the phrasing of a statement designed to measure attitudes, such as changing “Boys are better at science than girls” (an attitude) into:

Norms can also be measured by assessing whether social rewards or punishments are received for engagement in the given behaviour (i.e., social sanctions). For example, girls pursuing engineering in a context where assumptions are that only boys go into engineering may face harassment or discrimination from peers or even professors in that context.

Why are improvements in measurement needed?

Why does this distinction between attitudes and norms matter, conceptually and for measurement? Because growing evidence indicates that social norms, as well as individual attitudes, influence human behaviour. To affect gender inequalities at scale, shifting gender norms (rather than individual attitudes) may have more of a far reaching and sustained effect. Hence, we must measure these important targets of changes at national levels, and we must have such quantitative measures available for inclusion in global indices like GSNI.

The first step toward having these measures at scale is to have evidence-based social norms measures available for inclusion in our large-scale national surveys. To that end, we find the field sadly lacking. We recently analyzed social norms measures in just one area of gender equality, women’s economic empowerment, using measures from EMERGE, a one stop shop platform for open access (i.e. freely available) survey measures on gender equality and empowerment. (See the EMERGE Website to learn more, find measures for your work, and submit your measures.)

EMERGE has a compilation of 300+ survey measures on gender equality and empowerment for researchers and implementers, with measures crossing the areas of health, education, economics, politics, and other social spheres. Upon examining the available social norms measures (those showing face validity of assessing social norms and those defined by the authors of the measures as social norms), we found 26 measures purported to assess norms with respect to women’s economic empowerment. However, further examination of the measures by social norms experts on our team indicated that even these measures largely relied on attitudes, and that no measures focused on injunctive norms.

Where do we go from here as a field and in partnership?

Through these efforts, we hope to see expansion of gender norms measures, improved application of measurement science in development of these measures, and greater representation of actual gender norms measures in our national level indicators and global indices. Without strong quantitative measures, it will continue to be difficult to identify the norms that matter to achieving the SDGs and to assess the effectiveness of norms-shifting interventions. We at EMERGE encourage researchers working in this area to join us, and take a more active role in developing and testing social-norms measures for global gender equality.

About the authors

(All co-authors contributed equally and we have listed them out alphabetically)

Rebecka Lundgren, MPH, PhD – is a professor at the Center on Gender Equity and Health (GEH) at the University of California San Diego, leads the global secretariat of the Social Norms Learning Collaborative and supports its regional communities in Nigeria and East Africa. Her work seeks to advance social norms theory, measurement and practice, with a focus on developing practical guidance for implementing and scaling norms-shifting interventions to promote gender equity and prevent gender-based violence

Meredith Pierce, MPH – is a Research Project Manager supporting the research portfolios of Dr. Anita Raj and Dr. Rebecka Lundgren at University of California San Diego’s Center of Gender Equity and Health (GEH). Meredith’s most recent areas of work include focus on family planning, youth, research utilization, and HIV/AIDS. Prior to GEH, Meredith worked at Population Reference Bureau in International Programs and at USAID in the Office of HIV/AIDS and the Office of Population and Reproductive Health. Meredith holds a Master of Public Health from George Washington University.

Meredith Pierce, MPH – is a Research Project Manager supporting the research portfolios of Dr. Anita Raj and Dr. Rebecka Lundgren at University of California San Diego’s Center of Gender Equity and Health (GEH). Meredith’s most recent areas of work include focus on family planning, youth, research utilization, and HIV/AIDS. Prior to GEH, Meredith worked at Population Reference Bureau in International Programs and at USAID in the Office of HIV/AIDS and the Office of Population and Reproductive Health. Meredith holds a Master of Public Health from George Washington University.

Anita Raj, PhD – is a Tata Chancellor Professor of Society and Health and the Director of the Center on Gender Equity and Health (GEH) at the University of California San Diego. Her research, including both epidemiologic and intervention studies, focuses on sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, and gender data and measurement. She is also Principal Investigator on the EMERGE study referenced in this blog. She has served as an advisor to UNICEF, WHO, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She recently contributed to the Lancet series on Gender Equality and Health as an author and steering committee member; she co-led analyses of gender inequalities in health systems and the role of gender norms on health.

Anita Raj, PhD – is a Tata Chancellor Professor of Society and Health and the Director of the Center on Gender Equity and Health (GEH) at the University of California San Diego. Her research, including both epidemiologic and intervention studies, focuses on sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, and gender data and measurement. She is also Principal Investigator on the EMERGE study referenced in this blog. She has served as an advisor to UNICEF, WHO, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She recently contributed to the Lancet series on Gender Equality and Health as an author and steering committee member; she co-led analyses of gender inequalities in health systems and the role of gender norms on health.

Namratha Rao, MSPH – is a Research Program Manager/Consultant at the University of California San Diego’s Center of Gender Equity and Health, supporting the Center’s research portfolio in India. She has experience working in the HIV/AIDS, family planning, and WASH sectors and is extremely interested in health behavior change approaches to intervention and the intersections of environment, gender and health. Namratha received her Masters of Science in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University, MD.

Namratha Rao, MSPH – is a Research Program Manager/Consultant at the University of California San Diego’s Center of Gender Equity and Health, supporting the Center’s research portfolio in India. She has experience working in the HIV/AIDS, family planning, and WASH sectors and is extremely interested in health behavior change approaches to intervention and the intersections of environment, gender and health. Namratha received her Masters of Science in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University, MD.

to get the latest updates on new measures and guidance for survey researchers