By Nivedita Narain, Soledad Artiz Prillaman, and Natalya Rahman

By Nivedita Narain, Soledad Artiz Prillaman, and Natalya Rahman

Gendered imbalances in political spaces are widespread. While women may have attained universal suffrage, women are less present than men in most political institutions (World Bank 2012). Even when women are present, they often hold less political authority and are less likely to be heard than men (Karpowitz and Mendelberg 2014).

Empowering women in political spaces is not only critical for inclusive governance but also bears the promise of improved and responsive policy-making. Despite the need for and benefits from women’s political empowerment, few frameworks exist to assess and diagnose the extent of prevailing political power imbalances, particularly at the individual level. Further, unlike economic empowerment, political empowerment — the ability to choose when and how one interacts with political institutions — has received less scholarly attention. We propose a theoretical framework to conceptualize the process of political empowerment at an individual level and then introduce a new index of political empowerment measured through surveys conducted with individual women.

Conceptualizing Political Empowerment

Drawing on Kabeer (1999), we define political empowerment as the process by which those who have been denied the ability and agency to express their voice in the political system acquire such an ability. By political we refer to actions and beliefs that pertain to government institutions or are in service of engaging government institutions and policies (Burns et al. 2001).

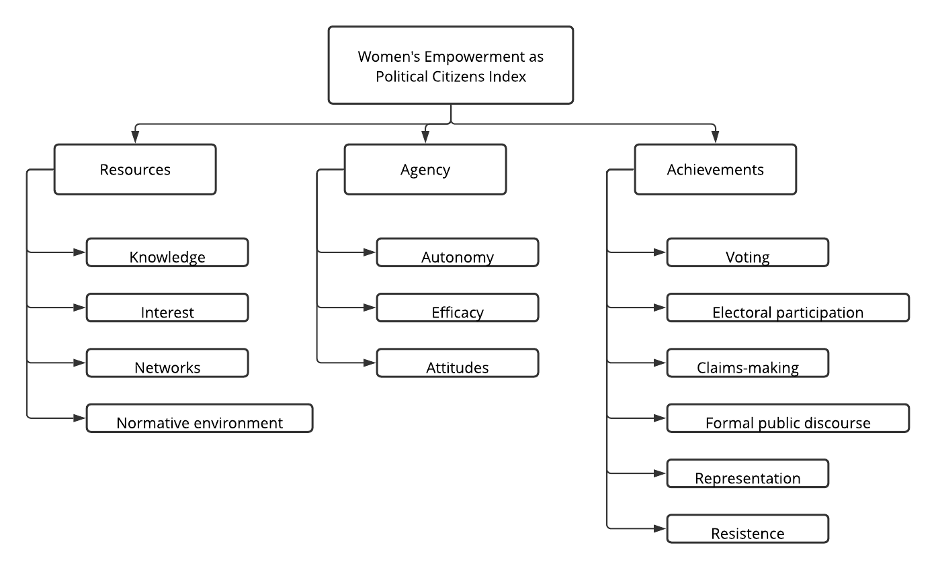

Kabeer (1999) suggests that the ability to exercise strategic life choices, or the process of empowerment, can be thought of in terms of three domains of social change: resources, agency, and achievements. We apply this framework to the domain of political action and argue that it is the accumulation of political resources, agency, and achievements that yields true political empowerment:

Figure 1 below maps this conceptual framework for political empowerment and highlights key components of each domain of political empowerment.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for political empowerment

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for political empowerment

The Women’s Empowerment as Political Citizens Index

Drawing on this conceptual framework, we develop a set of survey questions to construct a single measure of an individual woman’s political empowerment, which we call the Women’s Empowerment as Political Citizens Index (WEP Citizens Index). The index comprises 30 questions, [1] designed for the context of rural India, which are aggregated and weighted such that each of the three main domains receives equal weight. The final measure for each individual is an empowerment score that ranges from zero to one.

To test and evaluate the WEP Citizens Index, we conducted two surveys in 2019 in Betul district of Madhya Pradesh, India. Both surveys included all component measures of the index and were conducted with a random sample of adult women from rural villages. The first survey was conducted as per usual academic surveying practices with a team of external surveyors and included 540 women from 12 villages. The second survey was conducted as per a common practice of practitioner organizations and employed community-based data collectors (CDC) to survey 756 women from 16 villages, overlapping the 12 villages from the first survey.

Women’s Political Empowerment in Rural India

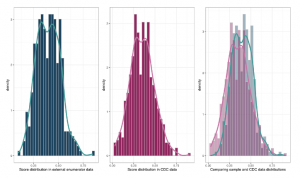

What can we learn from a measure of women’s political empowerment? Figure 2 shows the distribution of empowerment scores among women in our external enumerator and CDC survey respectively. Three key facts emerge:

Figure 2: Distribution of political empowerment for women across surveys

What drives political empowerment?

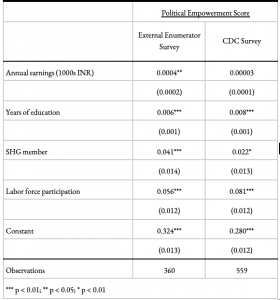

One test of the validity of our measure is how it correlates with previously theorized determinants of political participation. We examine whether higher income, increased labor force participation, higher levels of education, and self-help group membership positively correlate with political empowerment, all of which have been hypothesized to increase women’s political activity (Prillaman Forthcoming, Chibber 2002, Burns et al 2001).

Table 1 below reports the correlation between these indicators and our index of political empowerment using a basic OLS regression. Each of these conventional predictors of political participation is positively and significantly correlated with political empowerment. The effect of these predictors is also substantial; for example, SHG members in the external enumerator survey have a higher empowerment score by 0.04 on average. This might translate to one additional act of political participation. Similarly, women in the labor force in the CDC survey have a higher empowerment score by 0.08, which could translate to having one additional resource, for example, political interest. These strong and sizable predictions suggest that the WEP Citizens Index has construct validity.

Table 1: Predicting political empowerment with conventional correlates

What next?

Despite women’s political inclusion being a key goal of the SDGs, we have not had a framework for conceptualizing the holistic process of women’s political empowerment at an individual-level until now. Such a framework is critical for academics as they develop insights into the root causes and consequences of women’s political empowerment and for practitioners as they evaluate whether programs and policies have increased women’s political empowerment. While much more research is needed into the validity of this framework in different contexts and countries, we believe the WEP Citizens Index takes a step forward in conceptualizing the importance of women’s agency in political decision-making and demonstrating how such a conceptual framework can be deployed in realtime to understand progress at achieving this goal.

About the authors:

Nivedita Narain has worked with PRADAN for over three decades in a variety of leadership roles. She currently leads the research portfolio.

Soledad is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Stanford University. Her research focuses on gender, political representation, and development, with a focus in South Asia. She received a Ph.D. in Government at Harvard University.

Natalya is a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at Stanford University. She studies political behavior and development in South Asia.

References

Burns, Nancy, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Sidney Verba. The Private Roots of Public Action. Harvard University Press, 2001.

Chibber, Pradeep. “Why are some women politically active? The household, public space, and political participation in India.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 43.3-5 (2002): 409-429.

Kabeer, Naila. “Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment.” Development and change 30.3 (1999): 435-464.

Karpowitz, Christopher F., and Tali Mendelberg. The silent sex. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Prillaman, Soledad Artiz. “Strength in numbers: How women’s groups close India’s political gender gap.” American Journal of Political Science (Forthcoming).

World Bank. 2012. World Development Report: Gender Equality and Development.

[1] The full list of questions can be provided on request.

to get the latest updates on new measures and guidance for survey researchers