October 2021

By Miriam Harris

By Miriam Harris

The novel coronavirus 2019 pandemic (COVID-19) and public health responses to it have exacerbated inequities among socially structurally marginalized populations in the US. In Boston, this has been particularly true for unhoused people who use drugs where this population has experienced an increase in segregation, policing, and barriers to addiction, harm reduction, and HIV prevention services. This environment has operated to exacerbate an existing HIV outbreak in the city of Boston.

COVID-19 has also worsened structural challenges to HIV prevention among women who use drugs, a population that was already lacking HIV services pre-pandemic.1 These include worsening gender inequity, male domination in the street drug culture, sex work criminalization, and a lack of safe centers for harm reduction and addiction treatment access. While the impact of COVID-19 on HIV among women who use drugs remains unknown, this article draws on experiences caring for this population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Boston to reflect on challenges and launch calls for action.

Women who inject drugs before COVID-19 faced greater HIV risk. Though women comprised roughly one-third of all people who inject drugs, closer two-thirds of injection-related HIV infections occurred in women.2 In the US in 2018, women accounted for 62% of the 11,770 new HIV cases attributable to either heterosexual sex or injection drug use.3 HIV transmission during sex work and injection drug use were identified as primary drivers of the 2015-2018 HIV outbreak in Massachusetts4,5 and are believed to be responsible for the worsening HIV spread during the pandemic, however, data are lacking.

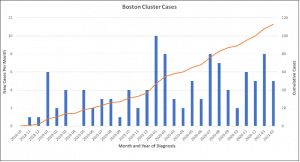

On March 15, 2021, a year into the pandemic and well into Massachusetts’s second COVID-19 wave, the Massachusetts state and city of Boston departments’ of public health released an alert declaring they were investigating a worsening HIV cluster among unhoused or vulnerably housed, people who inject drugs in Boston (Figure 1).6 The public health alert reported that 13 new HIV cases were identified between January 1, 2021, and February 28, 2021, alone. These new cases were a part of an ongoing HIV outbreak that had started in 2019, responsible for at least 113 new HIV infections in Massachusetts. Gender data is not yet available but based on provider experience most of the new HIV cases diagnosed during the COVID-19 have been among men rather than women, out of step with national trends.

Figure 1. New HIV Cases in Boston, Massachusetts from 2018-2021.[6]

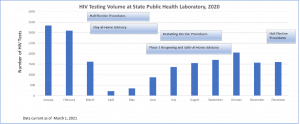

However, local experts fear the 13 new HIV cases reported in the alert are only the tip iceberg,7 and women are likely being underdiagnosed. Research has shown that women who use drugs are less likely to access street outreach, harm reduction, and addiction treatment where HIV testing and prevention occur because of stigma and safety concerns.8,9 Data from the state showed HIV testing dropped dramatically following COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories and while they have gradually increased testing has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2). Harm reduction staff report testing access among women in particular decreased because harm-reduction drop-in spaces closed and pivoted to active street outreach to reduce COVID-19 spread. Women need safety, warmth, and time for HIV testing, elements active street outreach could not offer.

However, local experts fear the 13 new HIV cases reported in the alert are only the tip iceberg,7 and women are likely being underdiagnosed. Research has shown that women who use drugs are less likely to access street outreach, harm reduction, and addiction treatment where HIV testing and prevention occur because of stigma and safety concerns.8,9 Data from the state showed HIV testing dropped dramatically following COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories and while they have gradually increased testing has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2). Harm reduction staff report testing access among women in particular decreased because harm-reduction drop-in spaces closed and pivoted to active street outreach to reduce COVID-19 spread. Women need safety, warmth, and time for HIV testing, elements active street outreach could not offer.

Figure 2. Massachusetts Department of Public Health HIV testing data, 2020[6]

Additionally, the same barriers preventing women equally benefiting from street outreach efforts, namely the male-dominated street culture and a lack of safety,10,11 have worsened in Boston since the pandemic. From 2020 through 2021 unhoused people who inject drugs have been increasingly segregated in a small geographic area in the city of Boston where they experience heighted police scrutiny and stigmatization. In tandem, the pandemic has significantly curtailed economic opportunities such as work in the service or restaurant industry, exotic dancing or sex work in clubs or massage parlors, panhandling, and income generated through shoplifting. These economic changes have disproportionately impacted women and may be related to reported increases in sex work and related physical and sexual violence against women in the area where the new HIV cases have been identified. Outreach staff fear women are benefiting less from the aggressive sterile syringe, condom, and HIV pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis outreach efforts as they are more difficult to reach and stay connected with.

Furthermore, injection use behaviors have changed in response to changes in the drug supply and street culture in Boston during the pandemic. Fentanyl and other toxic synthetic opioids replaced heroin predating COVID-19 and have been associated with more frequent injections related to its shorter duration of action.12,13 People who use drugs in Boston report the opioid supply became even more unstable during the pandemic changing injection practices. Methamphetamine use, which was rising pre-pandemic,14,15 continued to do so during the pandemic. The combination of the unstable opioid supply and increasing methamphetamine use resulted in people having to inject more frequently. Women have reported increased injection use to also stay awake and safe at night and during sex work. These changes have made accessing sterile syringes more difficult increasing HIV risks.

The COVID-19 pandemic severed to exacerbate drivers of HIV risk among women who use drugs and increased barriers to HIV prevention services in Boston. There is an immediate need to increase access to harm reduction and substance use treatment services to support HIV prevention among women who use drugs. Developing or scaling programs that are gender-specific, i.e., are designed for women, have long been called for and are needed now more than ever. Women-only, sex work-specific programs, and services that include violence prevention and other wrap-around sexual health services have been shown to increase engagement with addiction and HIV prevention services,16,17 and offer a road map to increasing HIV prevention for women who use drugs.

Policies that seek to reduce the root drivers of HIV are also urgently needed. The US must move to sanction safe consumption spaces which could significantly reduce HIV among people who use drugs. Access to low barrier housing, that is not contingent on abstinence from drug use, would interrupt HIV spread among unhoused people who use drugs. Low barrier housing for women experiencing intimate partner violence, violence during sex work, or sex work coercion is urgently needed. Such housing has historically been segregated from addiction and harm reduction services, rendering many women’s or family shelters inaccessible to women who actively use drugs. Without bold and immediate action, we risk worsening HIV outbreaks like the one occurring in Boston across the US. Women who use drugs must be prioritized in HIV responses if we wish to avoid further HIV risk inequity, morbidity, and mortality.

About the author:

Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and an addiction expert at Boston Medical Center. Her research is focused on the intersection of women’s health and addiction. She is a primary-care and addiction physician and attends on the General Medicine units and the Addiction Consult Service in the hospital.

References

1. Metsch L, Philbin MM, Parish C, Shiu K, Frimpong JA, Giang LM. HIV testing, care, and treatment among women who use drugs from a global perspective: progress and challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(0 2):S162-S168. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000660

2. El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA. Women who use or inject drugs: an action agenda for women-specific, multilevel and combination HIV prevention and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S182-S190. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000628

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (Updated). HIV Surveillance Report. 2020;31:1-119.

4. Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, et al. Opioid Use Fueling HIV Transmission in an Urban Setting: An Outbreak of HIV Infection Among People Who Inject Drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;110(1):37-44. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305366

5. Cranston K, Alpren C, John B, et al. Notes from the field: HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs—Northeastern Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;68(10):253.

6. Madoff L, Brown C, Lo JJ, Sánchez S. Public Health Alert to Boston Area Healthcare Providers: Increase in newly diagnosed HIV infections among persons who inject drugs in Boston. Published online March 15, 2021.

7. Taylor JL, Ruiz-Mercado G, Sperring H, Bazzi AR. A collision of crises: Addressing an HIV outbreak among people who inject drugs in the midst of COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;124:108280. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108280

8. Ayon S, Ndimbii J, Jeneby F, et al. Barriers and facilitators of access to HIV, harm reduction and sexual and reproductive health services by women who inject drugs: role of community-based outreach and drop-in centers. AIDS Care. 2018;30(4):480-487. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1394965

9. Boyd J, Collins AB, Mayer S, Maher L, Kerr T, McNeil R. Gendered violence & overdose prevention sites: A rapid ethnographic study during an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction. 2018;113(12):2261-2270. doi:10.1111/add.14417

10. Harris MTH, Bagley SM, Maschke A, et al. Competing risks of women and men who use fentanyl: “The number one thing I worry about would be my safety and number two would be overdose.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. Published online January 27, 2021:108313. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108313

11. Collins AB, Bardwell G, McNeil R, Boyd J. Gender and the overdose crisis in North America: Moving past gender-neutral approaches in the public health response. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2019;69:43-45. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.002

12. Ciccarone D. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2017;46:107-111. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.010

13. Talu A, Rajaleid K, Abel-Ollo K, et al. HIV infection and risk behaviour of primary fentanyl and amphetamine injectors in Tallinn, Estonia: implications for intervention. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.007

14. Wakeman S, Flood J, Ciccarone D. Rise in presence of methamphetamine in oral fluid toxicology tests among outpatients in a large healthcare setting in the northeast. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2021;15(1):85-87.

15. Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344-350.

16. Deering KN, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, et al. A peer-led mobile outreach program and increased utilization of detoxification and residential drug treatment among female sex workers who use drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(1):46-54. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.007

17. Wechsberg WM, Deren S, Myers B, et al. Gender-specific HIV prevention interventions for women who use alcohol and other drugs: The evolution of the science and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(0 1):S128-S139. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000627