Blog

By: Emma Samman and Lauren Pandolfelli

By: Emma Samman and Lauren Pandolfelli

In homes around the world, girls are performing more caregiving and chores than boys are. Globally, girls between the ages of 5 and 14 spend 160 million more hours every day on unpaid care and domestic work than boys of the same age.[1] Moreover, girls account for more than 60% of children who perform this type of work beyond age-specific thresholds.[2] And as children mature into adolescence, girls’ responsibilities intensify, widening the gender gap.

This unequal gendered distribution of unpaid care and domestic work has profound implications for children’s well-being. It limits girls’ time for learning, personal development, and leisure, stripping them of equal opportunities to thrive. In adulthood, these deprivations are likely to diminish their socioeconomic prospects, choices, and accomplishments – and the well-being of their children. And there are likely to impact on boys, too – e.g., a skewed sense of the value of girls’ versus boys’ time and as adults, limited roles as fathers and caregivers.

The unequal distribution of unpaid work has been documented in time use surveys worldwide. It is also increasingly recognised that gender norms heavily influence girls’ disproportionate engagement in such work. However, measures of these norms are lacking. Indeed, Emerge researchers’ scoping of 102 measures of women’s economic empowerment found that measures of gender norms were largely absent. They identified only nine measures of norms constructs, only three of which related to unpaid care and domestic work.

Building on previous research at UNICEF and beyond, UNICEF is focused on closing this gap by developing a standardized data collection tool to measure gender norms that influence children’s engagement in unpaid work. Our aim is to produce a short module that can be integrated into nationally representative surveys that collect vital data on children and women’s well-being, shedding light on how gender norms contribute to observed outcomes. The module aims to measure a set of common constructs that researchers have agreed to help quantify and capture how gender norms function in society.

Construct | Definition |

| Descriptive norm or empirical expectation | What I think others do |

| Injunctive norm or normative expectation | What I think others approve of/expect me to do |

| Reference group | Any group an individual uses as a standard for evaluating themselves and their own behaviour |

| Sanction (positive/negative) | Beliefs about the perceived benefits and rewards of adhering to a norm, or the perceived consequences of noncompliance |

| Attitude | What I think |

We believe that having such information can arm policymakers and practitioners with information to better understand how gender norms affect children and adolescents and their transitions into adulthood and craft policies and programmes aiming to redress girls’ disproportionate engagement in unpaid work.

Our evidence review suggests that having population-level standardized data could be potentially transformative in several respects. First, it could inform the design of policies, interventions, and services aiming to redistribute care and domestic work within households – including labour market interventions (e.g., family-friendly policies such as maternity, paternity, parental leave), social protection, investments in care-related infrastructure (e.g., childcare facilities and support), support for girls’ education and the provision of labor-saving technologies to households. Second, it could enable a richer understanding of how restrictive gender norms predict how girls and boys spend their time and how changes in these norms influence children’s well-being, including outcomes in education and health and transitions to adulthood. Third, it would allow assessment of how norms are distributed within a population, giving insights into how policies, programs, and services can be improved and targeted. Fourth, it could prompt evidence-based shifts in institutional policies, power relations, and media discourse, which powerfully influence gender relations. Finally, it could catalyze changes within communities and households to redress unequal workloads.

Our work to date has focused on an in-depth review of the evidence on gendered norms and a mapping of existing data collection tools. This has enabled us to understand how gender norms related to children’s engagement in unpaid work are conceptualized and measured; and the strengths and methodological limitations of existing measures. Based on this review, we have developed a household survey module and corresponding set of indicators for cognitive and field testing. In collaboration with the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, we will conduct the first testing in the Mutare region of Zimbabwe later this year. Following this testing, and with funding from the EMERGE project, we will analyse the validity and reliability of the norms measures and refine the module for testing in other regions before finalizing.

For more information, visit https://data.unicef.org/topic/gender/gender-norms-and-unpaid-work/

[1] United Nations Children’s Fund, Harnessing the Power of Data for Girls: Taking stock and looking ahead to 2030, UNICEF, New York, 2016.

[2] International Labour Office and United Nations Children’s Fund, Child Labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward, ILO and UNICEF, New York, 2021.

About the authors:

Emma Samman is a Research Associate with ODI and an independent consultant, working with UNICEF. Her research focuses on the analysis of poverty and inequality, particularly gendered inequalities, and household survey design. She has worked extensively on the quantitative measurement of gender norms, and their drivers and impacts.

Lauren Pandolfelli is a Statistics Specialist in the Division of Data, Analytics, Planning and Monitoring (DAPM) at UNICEF, where she leads the division’s technical work to improve the quality, analysis and availability of gender data on women and children.

Image: “A girl removes laundry from the line at a camp for migrant workers near the city of Adana in Adana Province.” © UNICEF/UNI42696/LeMoyne

By: Nadia Diamond-Smith

By: Nadia Diamond-Smith

By: Elettra Baldi, Arnab K Dey, Jennifer Yore and Lauren Bredar

By: Elettra Baldi, Arnab K Dey, Jennifer Yore and Lauren Bredar

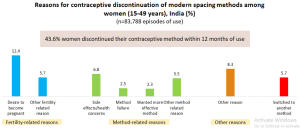

By Chhavi Sodhi

By Chhavi Sodhi

By Rebecca S. Levine, Zaharah Namanda, Amy V. Bintliff & Anita Raj

By Rebecca S. Levine, Zaharah Namanda, Amy V. Bintliff & Anita Raj

By Nabamallika Dehingia1, Lucina Di Meco2, Anita Raj1

By Nabamallika Dehingia1, Lucina Di Meco2, Anita Raj1

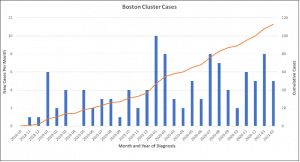

By Miriam Harris

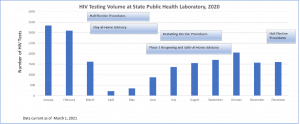

By Miriam Harris However, local experts fear the 13 new HIV cases reported in the alert are only the tip iceberg,7 and women are likely being underdiagnosed. Research has shown that women who use drugs are less likely to access street outreach, harm reduction, and addiction treatment where HIV testing and prevention occur because of stigma and safety concerns.8,9 Data from the state showed HIV testing dropped dramatically following COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories and while they have gradually increased testing has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2). Harm reduction staff report testing access among women in particular decreased because harm-reduction drop-in spaces closed and pivoted to active street outreach to reduce COVID-19 spread. Women need safety, warmth, and time for HIV testing, elements active street outreach could not offer.

However, local experts fear the 13 new HIV cases reported in the alert are only the tip iceberg,7 and women are likely being underdiagnosed. Research has shown that women who use drugs are less likely to access street outreach, harm reduction, and addiction treatment where HIV testing and prevention occur because of stigma and safety concerns.8,9 Data from the state showed HIV testing dropped dramatically following COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories and while they have gradually increased testing has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2). Harm reduction staff report testing access among women in particular decreased because harm-reduction drop-in spaces closed and pivoted to active street outreach to reduce COVID-19 spread. Women need safety, warmth, and time for HIV testing, elements active street outreach could not offer.

By Divya Bhardwaj

By Divya Bhardwaj

By Nivedita Narain, Soledad Artiz Prillaman, and Natalya Rahman

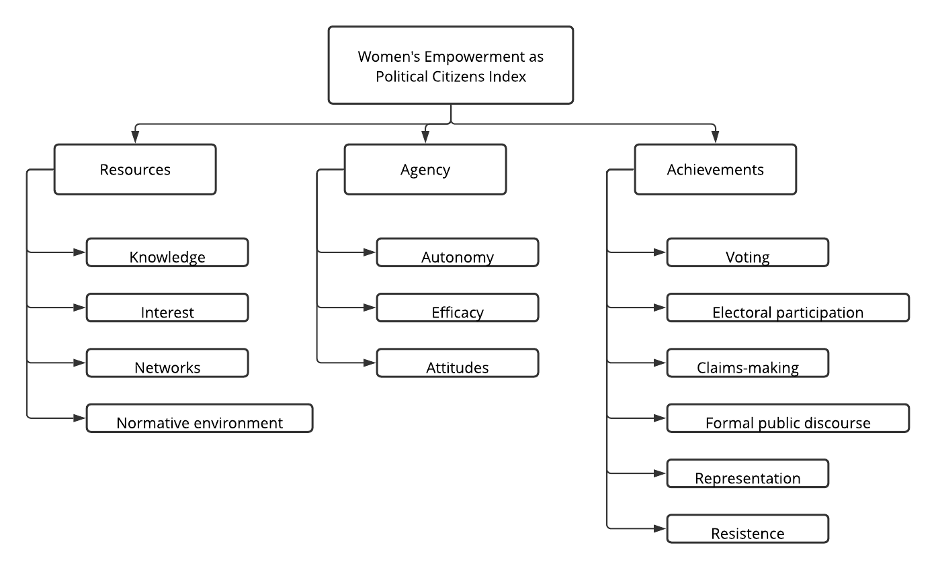

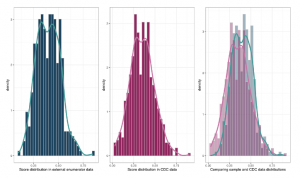

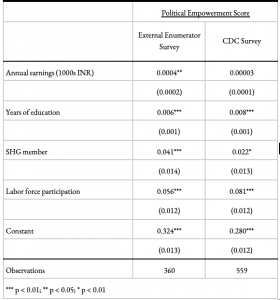

By Nivedita Narain, Soledad Artiz Prillaman, and Natalya Rahman Figure 1: Conceptual framework for political empowerment

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for political empowerment

By Swetha Sridhar

By Swetha Sridhar